|

|

Monsieur Harel, director of the theatre of the Porte Saint-Martin, had made it clear: ‘I want an air entirely subservient to the words’. Hence there was no question of accepting, for the première of Lucrèce Borgia (12 february 1833) a music ‘one would listen to and which would distract from the drama’, even if this was wanted by the author Hugo, personally. Yet, in this piece, music occupies quite a special place, since it brings about the coup de théâtre which leads to the dénouement with this duet between the drinking-song and the De Profundis, between the monks’ procession and the accents of orgy whose lines were the poet’s and the notes the conductor’s, Alexandre Piccini, grandson of the so-called Gluck’s rival who was content to transcribe the rhythm of the refrain on the basis of the primitive beat hammered by the dramatist on a table corner. It is said that Meyerbeer and Berlioz had also intended to write this music but Piccini was able to produce something as plain as desired by Director Harel: Victor Hugo was 31 years old. The Concert Historique of 13 january counted among its listeners the man in France who was considered, wrongly so, as the most closed to music with his famous ‘I only like the barrel organ and the tunes of Dédé’ (alias his daughter Adèle, in the absence of Léopoldine?); but are there not legends which last for centuries?

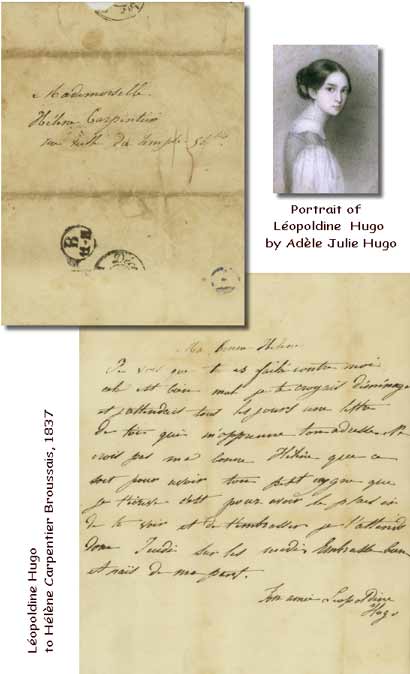

All Hugo’s dramas contain one or several songs. He writes some himself or approaches composers. In 1831, the July government commissions a Hymne from him to celebrate the anniversary of ‘Those who piously died for the Fatherland’. Hérold (Prix de Rome 1812), composer of Zampa, of Pré aux Clercs and of the ballet La Somnambule (1927) is asked to provide the music. Hugo writes to him thus: ‘I don’t know whether you would feel like doing something with the lines I have had the honour of sending you, and I do invite you not to do anything with them. If, however, you do decide to give soul and life to these dead words, I herewith forward to you two linesI have changed...’. The composers converse with the Poet with due coquetry. Charles Gounod writes to him from Saint-Cloud, 39, route Impériale: ‘Dear Sir and very illustrious Master, Your gigantic way of moving, like worlds, ideas and images, this organ of the mind all whose keyboards resound under your fingers, all this throws such powerful sonority into the soul that henceforth one does not dare add one’s weak note, lost as it would be in the hurricanes unleashed by you’. In 1839, Gasparo Spontini, famous author of La Vestale (6 december 1807) turns to him in these terms: ‘I, too, would have some ideas to put to you in order to facilitate your search for a suitable opera subject, passionate, voluptuous, with continual ballets, religious ceremonies, with war hymns, songs, heroic ballads, voluptuous huntresses...’. A self-confident 32-year-old, Ernest Reyer, who was to become famous with Sigurd and Salammbô, takes the liberty, on 22nd december 1855, to ask for his authorization to set to music the Vieille Chanson du Jeune Temps, recognizing at the same time: ‘it does not need this at all, that is true, but I would be quite proud to shelter my little-known name under your benevolent renown’. Permission granted nine months later, Reyer expresses profuse thanks: ‘... I shall thus take a share of the legitimate and resounding success of theContemplations’. To Gounod’s organ responds the piano (‘this wooden animal’) of Mademoiselle Louise Bertin, very dear and faithful friend of the poet (‘... you whose flaming hand makes the piano speak the language of your soul’) and to whom the poet spent hours listening when she played the chorus from Armide by Gluck: ‘never in this handsome place...’, Hugo who already appreciated very much the hunter-choruses in Weber’s Euryante: ‘perhaps what is most beautiful in all music’. ‘No music disposal along my lines’, Victor Hugo warned. However, had he not himself given authorization to Louise Bertin, in 1836 (he was 34 years old), to write a score for the libretto of the opera La Esmeralda, a libretto he himself had drawn, and put into verse, from his novel Notre-Dame de Paris, knowing full well that the Director of Paris Opera, doctor Véron (known as Torti Coli), would not be able to refuse anything to the Bertin family who owned the Journal des Débats, and thus dictated to the government and would go ahead launching it. La Esmeralda was hence performed six times in its entirety, with ballet; from the seventh performance, three out of four acts were altered, then the first act only was performed. The 25th performance was the last one. Victor Hugo was delighted to stand aside from the music (‘he who is nothing’, as he said, speak-ing of himself, while invoking the illustrious precedent of Molière and Corneille, librettists of the opera-ballet Psyché, 1671). Victor Hugo considered Louise Bertin’s music ‘brilliant drapery’; the critic of the journal Le Voleur compared the lady-musician to Meyerbeer; as for the stage sets, Victor Hugo planned to ‘break down the theatre so that the towers of the church Notre-Dame be visible as the crow flies’. Only the Journal de Paris dared dampen the enthusiasm (not to say, cast shadow on all these beams of light: ‘... if it is out of galanterie that the poem’s author has effaced himself, one has to agree that he has reached his aim marvellously: perhaps he can even flatter himself to have gone beyond it’. Should the bad-tempered remark: ‘No music disposal along the lines of my poetry’ date from this epoch? Amilcare Ponchielli (La Gioconda, Marion Delorme), Giuseppe Verdi (Ernani, Rigoletto) found inspiration in Angelo,Tyran de Padoue and in Le Roi s’amuse. With regard to Rigoletto, it is well-known that the Poet, having listened to the quartet of the last act, exclaimed enthusiastic: ‘If in my plays, I too, managed to make four characters speak at the same time and the audience perceived their words and feel-ings, I would obtain the same effect’. Later, others still, among them great melody-composers like Camille Saint-Saëns (Guitare), Liszt (Oh! Quand je dors) or Gabriel Fauré (Mai, Le Papillon et la Fleur, Rêve d’amour, Puisque ici-bas toute âme, Dans les ruines d’une Abbaye...) made efforts to illustrate this definition of melody by Olympio himself: ‘a melody is for the ear what the perfume of a flower is for the sense of smell: an inexpressible mixture of sensations and the ideal’ (in Tas de Pierres). Hugo certainly took no interest in the Théâtre Italien. He did not like Rossini, he did not like La Donna del Lago, hence he did not like music. Do we not discover, in Les Rayons et les Ombres: Palestrina, Gluck, Mozart, Weber, not bad at all. As for Beethoven: ‘that is the German soul’, adding: ‘This deaf man heard the infinite... This being who does not perceive the word, engenders song. His soul, outside of him, becomes music. These dazzling symphonies, tender, delicate and profound, these marvels of harmony, these sonorous radiations of the note and of the song, are coming out of a head whose ear is dead. We seem to see a blind god create suns...’ These suns which, in the end, were perhaps none other than the unsterbliche Geliebte (the immortal Beloved) of a musician, in whom interest was shown, more or less sostenuto, by Giuletta Guicciardi, Thérèse Brunswick, the singers Magdalena Wilmann and Christine Gerhardi, the countess Deym, Thérèse Malfatti and Amalie Sebald (an amateur singer much appreciated by Weber). There will be no question of Wagner, unless through the prism of the foremost of the female admirers of the author of Tristan, Judith Gautier from Tarbes, whom Hugo had known at Place Royale (he lived at n° 6 and Théophile Gautier at n° 8) and to whom he will dedicate the most beautiful of the five sonnets that escaped his pen: Hugo-Corneille was 70 at the time of these lines. Booz was thinking of Ruth, of the family circle, of the sad, soiled foreheads, of the child who appears, of the child who sings: The little Victor was thinking of his own mother who had fallen seriously ill and at whose bedside he wrote Han d’Islande, the novel of his engagement, and who died on 27 june 1821; he was thinking of this well-known evening of 29 june, day of his mother’s funeral and of the moment when, mad with pain, Ordener runs to Ethel’s dwelling; noisy music was coming out of the illuminated windows of the Hôtel des Conseils de guerre, rue du Cherche-Midi, residence of Pierre Fouché, head of department in the Ministry, knight in the Legion of Honour and of Anne-Marie Victoire Asseline, his wife, happy parents of Adèle Julie, fiancée of the young Victor. They played billard, a ball was given there and Adèle... was dancing. Throughout his life, Victor Hugo will have a passion for billard (even if ‘of a strange sort’): there are wounds to the heart that ooze music. Claude d‘Esplas (The Music Lesson) |

ADG-Paris © 2005-2024 - Sitemap